Berkson’s paradox for expertise

Why was all the best information about Coronavirus coming from niche twitter accounts while the institutions with all the expertise got it wildly wrong? All you have to believe in order to explain this is that the best people within our journalism and governance institutions believe they have better career options elsewhere. The rest follows.

The best minds of our generation

The Silicon Valley entrepreneur scene (as differentiated from the broader sphere of tech employees) was alarmist about Coronavirus for months in early 2020 while public health authorities, journalists and elected officials were saying the flu was the real menace. Now everyone is righteously angry at the loosely defined but easily recognizable class of bureaucratic and journalistic knowledge gatekeepers that have the privilege of being called experts. Regardless of why, Balaji was right, Kara Swisher was wrong, and the CDC should have responded the same way N. N. Taleb enthusiasts did.

There’s a narrative that America’s iconic 20th century institutions have turned sclerotic because they’ve been hollowed out of human talent. The observation comes from both sides of the political spectrum, like journalism academics blaming a decline in student interest on Harry Potter’s “unnecessarily pessimistic view of journalism” and the blunt Trump 2016 campaign line “One of the key problems today is that politics is such a disgrace, good people don’t go into government.”

Jeffrey Hammerbacher took it further and pointed fingers at a cause with his iconic observation “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads.” The Washington Post complains that “more than 45 percent of senators who have left office since 1992 have served on the board of a publicly traded firm.” Hammerbacher is observing a selection bias against going into public service and the Washington Post is observing a trend preventing many from staying in public service, but the end result is the same.

Let’s suppose they’re right and there’s some set of career opportunities more appealing than entering into the institutions of mass media and American bureaucracy. Let’s suppose the smartest students are choosing STEM instead of public policy and let’s suppose the most ambitious see government posts as just stepping stones to board seats and cushy partner roles. It would at least explain some of the institutional decay everyone talk about. But by itself, it wouldn’t explain the American Covid response. It doesn’t explain why so many people with small pulpits saw precisely what was coming while our leaders and would-be-thought-leaders chastised people for buying masks. The burning question isn’t why everyone got it wrong, it’s why everyone with a megaphone shouted wrong answers while thousands of quiet observers got it right.

An imperfect but useful model

There’s a phenomenon called Berkson’s Paradox where a genuine correlation between two variables appears to invert to an observer. It goes like this. Let’s reduce every American to two usefully ambiguous dimensions: ability and credentialing. Specifically,

- ability to recognize the threat of coronavirus

- leverage in the form of credentials for sharing their view

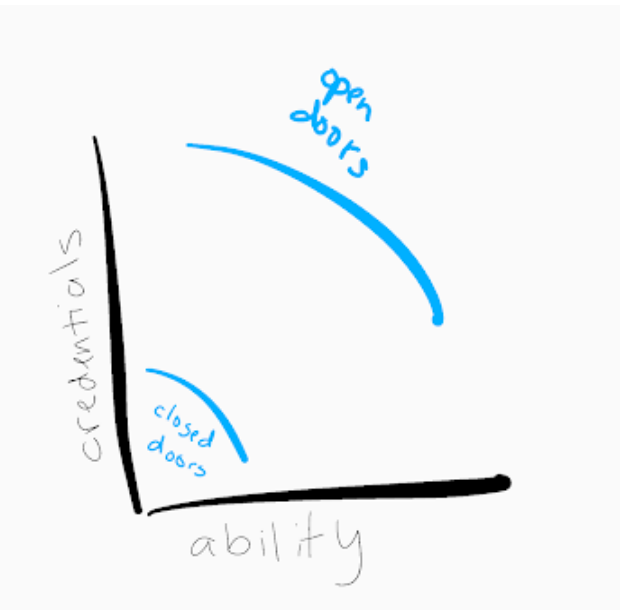

Those who are exceptionally capable and have the most leverage have doors open to them- new careers and positions and industries. On the other hand, those who lack both are predominantly invisible to us and not positioned anywhere we might end up paying attention to them.

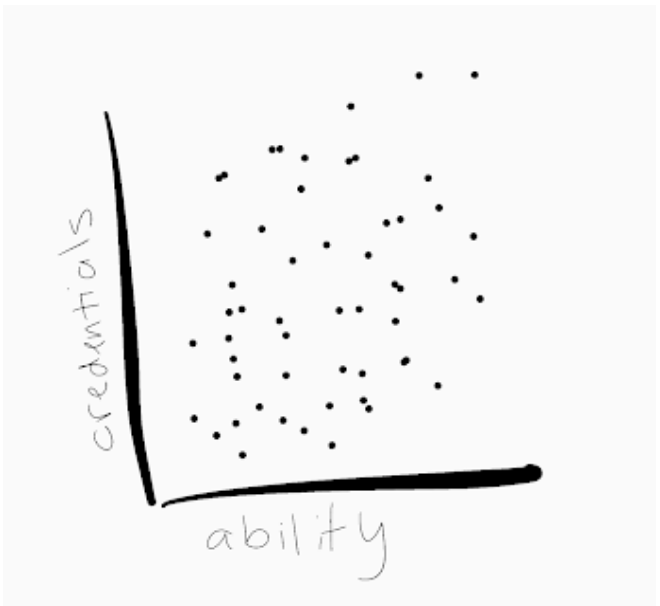

Now let’s put some people on the graph. They’re not random, we of course think there ought to be some causation between ability and credentialing, but we’re appropriately humble and cynical enough to know it will be a very messy correlation.

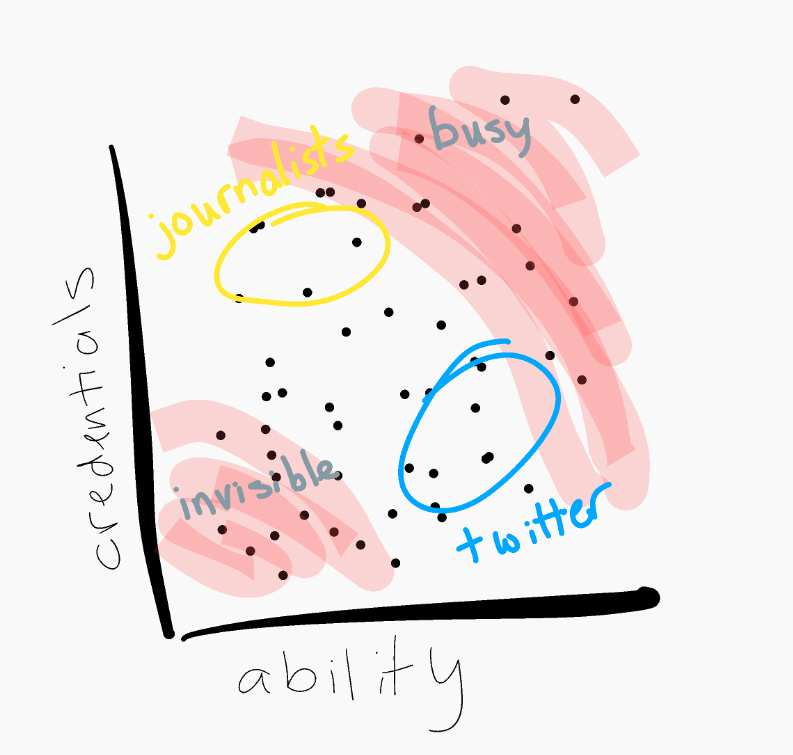

Let’s search among these points for the people who we’ve seen talking about Coronavirus. Those in the lower left are probably not on our radar. Those with enough credentialing, say a byline at Vox or a management role at the CDC, have a good chance to show up on our radar, as do the Joe Normans and Balaji Srinivasans of the world who only have Medium and Twitter accounts but manage to say something interesting enough to grab your attention. Of course all four of these examples have a pulpit and a good bit of talent, but perhaps not all in equal quantity. Finally we get to the upper right corner, where everyone is taking private equity jobs or not showing up at all because they’re making you click ads or all the other desirable roles that don’t involve publicly commenting on Coronavirus.

Instead of the reasonable expectation that credentials are a proxy for the value of an opinion, we see the reverse correlation. This is Berkson’s Paradox: our expectation that people in positions of authority are reliable sources appears inverted and those who have the most obvious claims to expertise are in fact the least qualified. Maybe it’s just in my bubble, but the outrage I’m seeing isn’t just that our civic leaders got this wrong, it’s that people on the ground got it right and no one listened. The right takeaway isn’t that all media and government spokespeople are idiots. It’s just that when you take the veneer of expertise at face value, the “expertise” label becomes worse than useless.

Institutional decline

All you have to believe for this explanation to hold water is that highly talented people are either no longer drawn to bureacratic and jouranlism roles or that once they get there, the best people see greener pastures elsewhere. From that point, there are lots of theories like O-ring theory or talent density to explain why even slight declines in talent cause massive drains in the effectiveness of institutions. The interesting part is that the hypothesis is unique to this class of people. Presumably being a doctor in the US is sufficiently prestigious that we’re keeping our best doctors as doctors and being a bureaucrat in Singapore is an attractive career. So what happened to the so-called thought leaders in the US?

I have two theories.

- Government and journalism were always hollow institutions, we’re just didn’t discover it until the internet and social media took away the experts’ monopoly on mass communication. This hypothesis has a lot in common with Martin Gurri’s Revolt of the Public thesis.

- Government and mass media institutions used to be genuine seats of power that attracted America’s best talent. As government agencies entered their current period of remarkably stable size and legacy media organizations began to lose ground, these careers became less attractive at the same time financialization made other managerial careers more attractive. The pipeline of talent shifted towards finance, management, tech and other lucrative industries.